Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Operationalising Moral Foundations Theory

2

‘Moral-foundations researchers have investigated the similarities and differences in morality among individuals across cultures (Haidt & Joseph, 2004). These researchers have found evidence for five >1 fundamental domains of human morality’

(Feinberg & Willer, 2013, p. 2)

Q

There may be cultural variations on what is, and what isn’t, an ethical issue.

So we can’t assume in advance that we know for sure what is ethical and what isn’t.

But if we don’t know what is ethical and what isn’t, how can we study cultural variations in it?

individual foundations

harm/care, (in)equality, (dis)proportionality

binding foundations

betrayal/loyalty, subversion/authority, and impurity/purity

Graham et al. (2011), Atari et al. (2023)

care

I believe that compassion for those who are suffering is one of the most crucial virtues.

We should all care for people who are in emotional pain.

Everyone should try to comfort people who are going through something hard.

purity

People should try to use natural medicines rather than chemically identical human-made ones.

I think the human body should be treated like a temple, housing something sacred within.

I believe chastity is an important virtue.

(Atari et al., 2023)

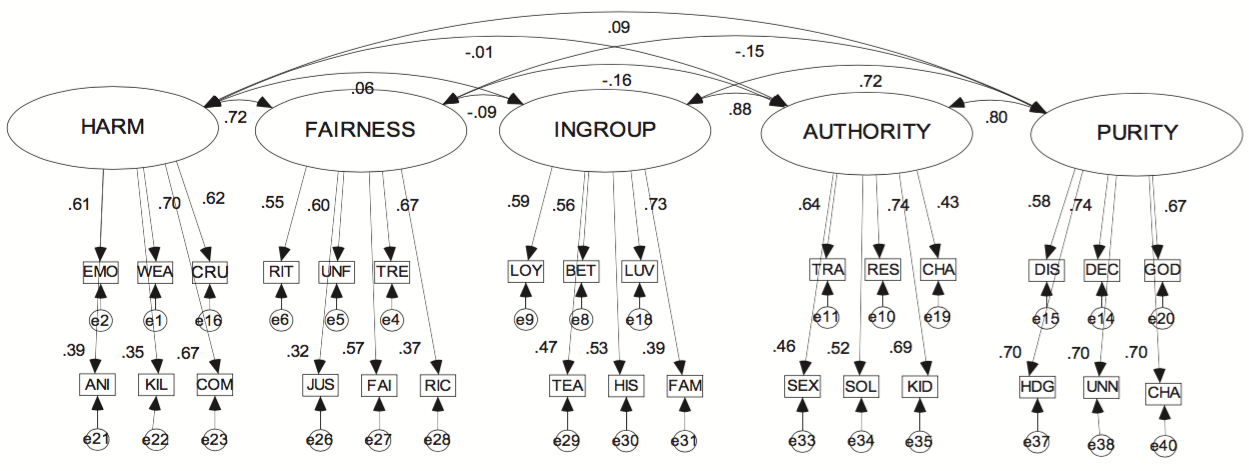

People’s views about care cluster together,

as do people’s views about purity;

and these two sets of views appear to be distinct.

Atari et al. (2023, p. fig 1)

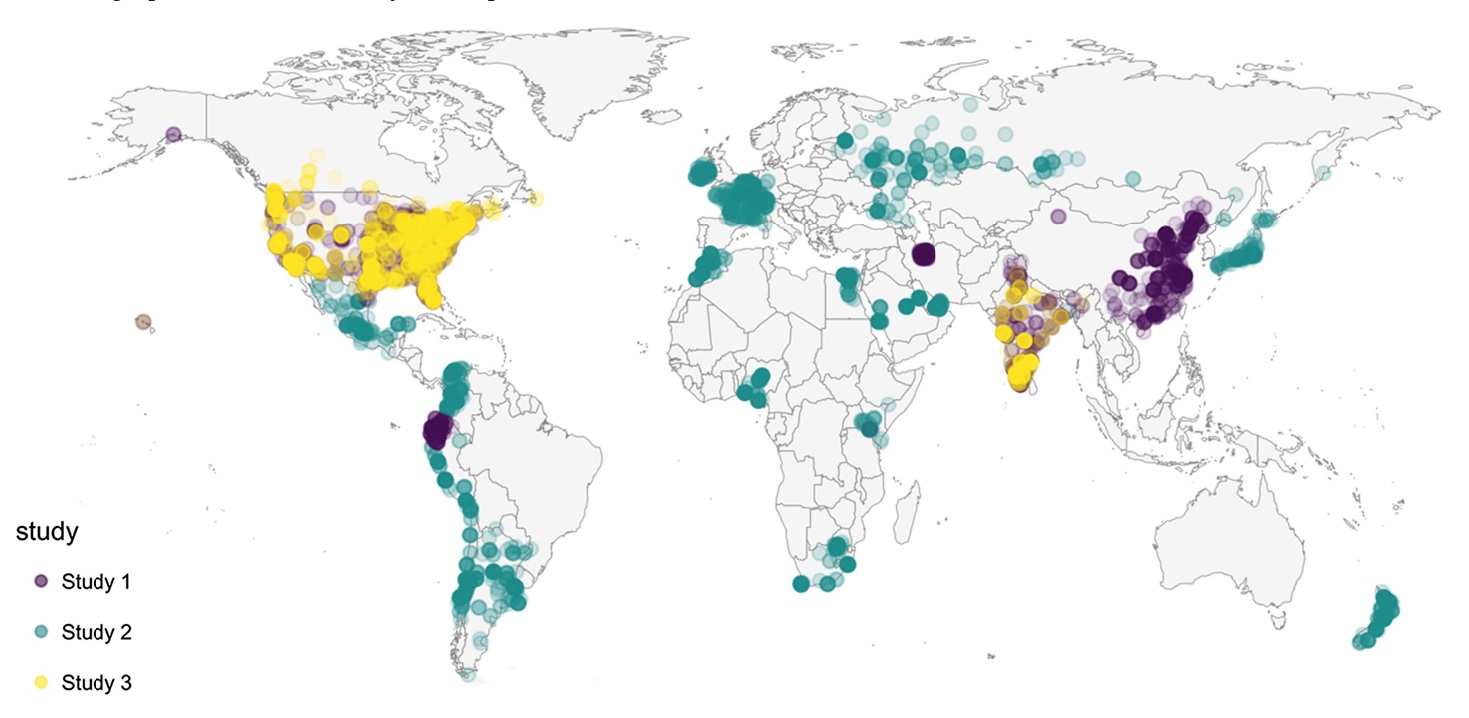

external validity

external validity

Atari et al. (2023, p. fig 8)

Q

There may be cultural variations on what is, and what isn’t, an ethical issue.

So we can’t assume in advance that we know for sure what is ethical and what isn’t.

But if we don’t know what is ethical and what isn’t, how can we study cultural variations in it?

Have we answered this question?

fieldwork -> hypothetical model -> CFA -> revise model -> ...

Graham et al, 2009 figure 3

Does this reflect

merely differences in how people interpret the questions

or substantial differences in their moral foundations?

‘A finding of measurement invariance would provide more confidence that use of the MFQ across cultures can shed light on meaningful differences between cultures rather than merely reflecting the measurement properties of the MFQ’

Iurino & Saucier, 2018 p. 2

metric invariance - you can compare variances

scalar invariance - you can compare means (eg ‘conservatives put more weight on purity than liberals’)

summary of requirements

model fit (CFA)

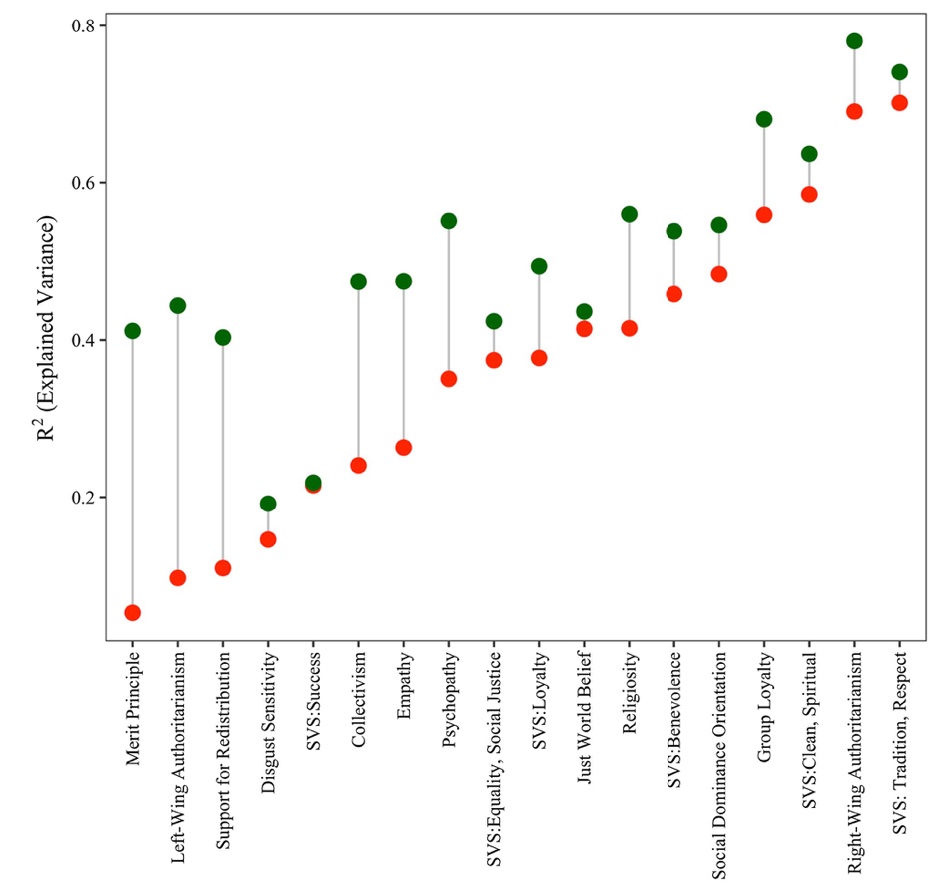

predictive power

measurement invariance

... and others (test-retest reliability, ...)

MFQ-2 : from 2023 (Atari et al., 2023; Dogruyol et al., 2024)

MFQ-1: from 2007 (Haidt & Graham, 2007)

Davis et al. (2016): no scalar invariance for Black people vs White people

Atari, Graham, & Dehghani (2020): scalar non-invariance for US vs Iranian participants

Doğruyol, Alper, & Yilmaz (2019): metric non-invariance for WEIRD/non-WEIRD samples

Nilsson (2023): non-invariance for class within Sweden

Iurino & Saucier (2020): problems with fit

MFQ-1 (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009, p. Appendix B)

harm

If I saw a mother slapping her child, I would be outraged.

It can never be right to kill a human being.

Compassion for those who are suffering is the most crucial virtue.

The government must first and foremost protect all people from harm.

purity

People should not do things that are revolting to others, even if no one is harmed.

I would call some acts wrong on the grounds that they are unnatural or disgusting.

Chastity is still an important virtue for teenagers today, even if many don’t think it is.

The government should try to help people live virtuously and avoid sin.

‘some of the [...] items may conflate moral foundations with other constructs such as religiosity or racial identity.’ (Davis et al., 2016, p. e29)

MFQ-2 : from 2023 (Atari et al., 2023; Dogruyol et al., 2024)

MFQ-1: from 2007 (Haidt & Graham, 2007)

Davis et al. (2016): no scalar invariance for Black people vs White people

Atari et al. (2020): scalar non-invariance for US vs Iranian participants

Doğruyol et al. (2019): metric non-invariance for WEIRD/non-WEIRD samples

Nilsson (2023): non-invariance for class within Sweden

Iurino & Saucier (2020): problems with fit

summary of requirements

model fit (CFA)

predictive power

measurement invariance

... and others (test-retest reliability, ...)

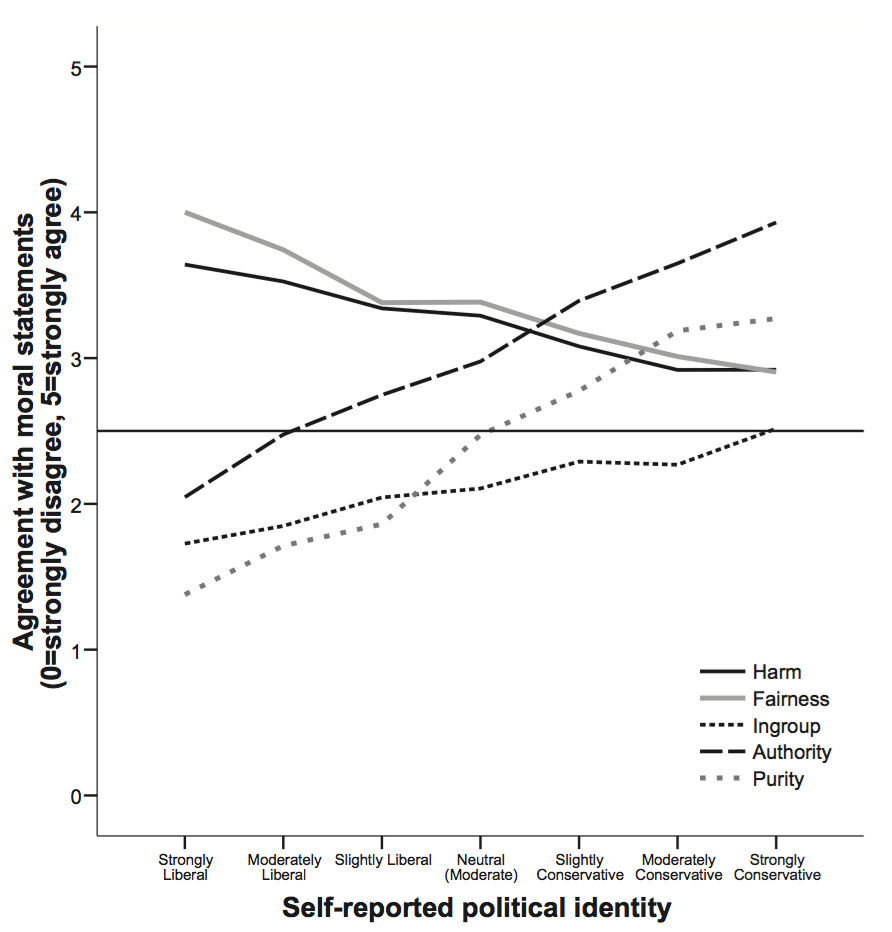

MFQ-2

fairness -> equality and proportionality (six factors)

scalar invariance ✓?

liberals differ from conservatives in scoring:

higher on care and equality

lower on proportionality, loyality, authority and purity

(Atari et al., 2023)

partial replication: Dogruyol et al. (2024)

Q

There may be cultural variations on what is, and what isn’t, an ethical issue.

So we can’t assume in advance that we know for sure what is ethical and what isn’t.

But if we don’t know what is ethical and what isn’t, how can we study cultural variations in it?

Have we answered this question?

fieldwork -> hypothetical model -> CFA -> revise model -> ...

2

‘Moral-foundations researchers have investigated the similarities and differences in morality among individuals across cultures (Haidt & Joseph, 2004). These researchers have found evidence for five >1 fundamental domains of human morality’

(Feinberg & Willer, 2013, p. 2)